Thalen had spent more years in the boathouse than in his own home.

It wasn’t a building like the others: it rose over the harbor like a sleeping giant, all stonework, with massive arches and pillars that sank all the way to the seabed. Almost as long as a city square, it stretched over the water like a closed bridge — a stone belly where boats could enter to be repaired.

And it wasn’t the only one.

All across the capital, there were similar structures, relics of the old world. Some were crumbling, cracked and overgrown with weeds; others, like the boathouse, seemed to resist time better than any modern building. They all shared the same unsettling trait: they appeared to be carved from a single block of stone, with no visible joints, no sign of tools.

Thalen remembered when they had restored it, decades ago. He had still been a young man, and that had been the largest public works project the city had attempted in generations. For months the boathouse had been full of architects, masons, engineers.

He had stayed there, watching, as their voices echoed between the columns. He didn’t understand much about masonry, but he heard them speak in low voices, with respect and a hint of fear. They said the structure was unlike any other: its foundations had been found intact, without a single sign of collapse, as if they had been laid only the day before. Some claimed the stone wasn’t even from the region, but of a material no longer found for centuries.

“It’s as if it grew here,” one architect had said, incredulous, on a day he thought no one was listening.

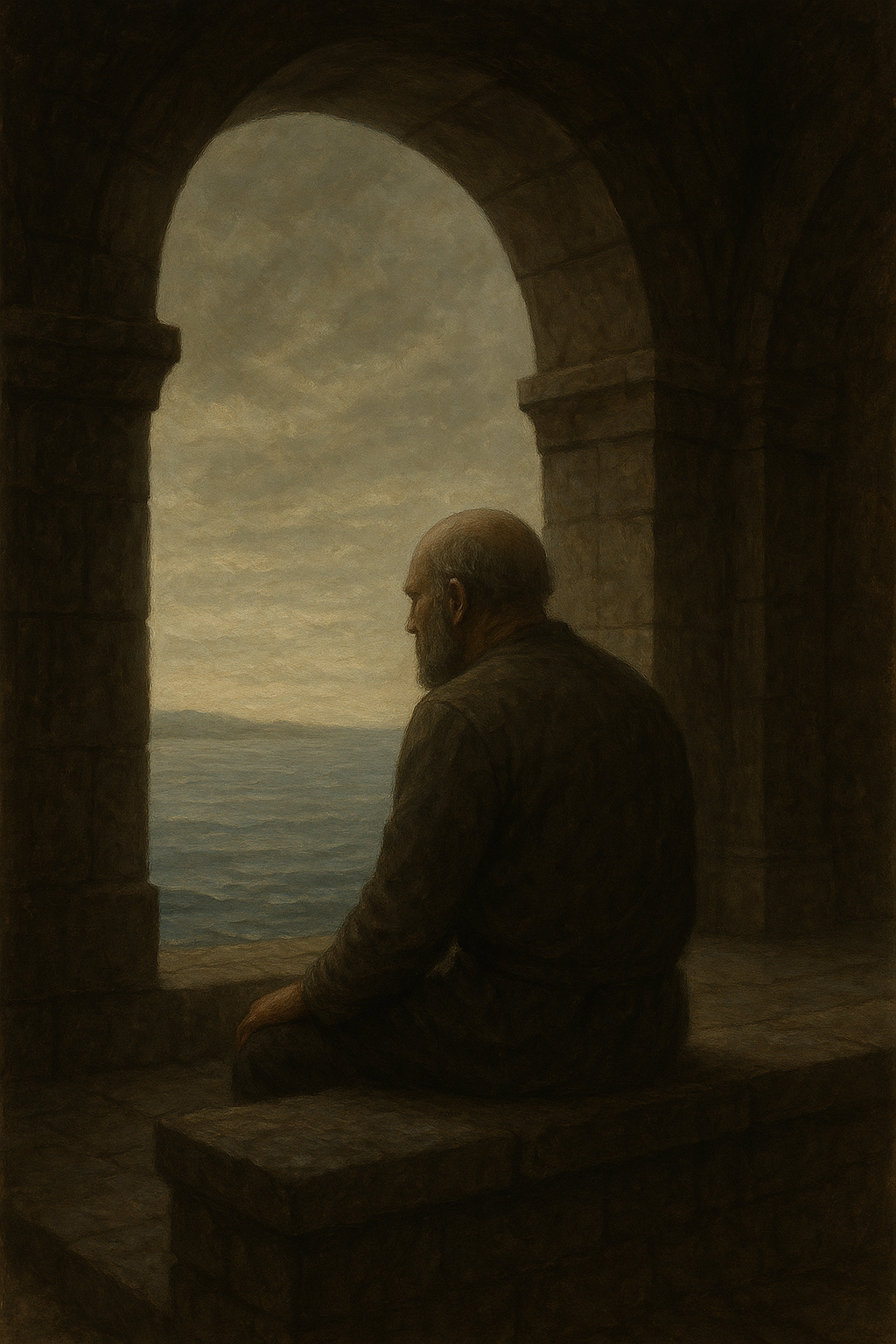

Now, in the evenings, Thalen sat on the stone dock, pipe lit, staring into the darkness below him.

He had chosen this place for the end of his days.

His two sons had disappeared two days earlier, during the attack on the port. No bodies had been found. The first whispers among sailors and dockhands spoke of explosions, fire, screams drowned in water. And the government? It could do very little. Not right away, at least.

Thalen knew his own time was nearly up.

There were no nets left to pull, no boats to mend. Only the sound of the water lapping against the columns, steady and slow like a breath.

Sometimes he heard a deep echo rising from the foundations, a dull rumble that didn’t seem to come from the sea. He never told anyone.

He just muttered:

“Old world, old secrets. They can keep their answers.”

Thalen rose with a slow, almost mechanical movement.

He had made up his mind.

There was nothing left to wait for.

He took the old rope he kept coiled by his toolbox and unrolled it carefully. Gravity would do the rest — and in some way, that thought calmed him.

He wandered through the boathouse, searching for a suitable spot: a hook, a beam, any anchor point. But the walls, as always, were smooth as glass. No cracks, no place the rope could hold.

He ran his hand along the stonework, feeling the unnaturally smooth, cold surface beneath his fingers. It was as if someone had polished it just the day before, not centuries ago.

Then he saw it.

A thin line, almost invisible, running along part of the wall. It wasn’t a natural crack. It was too straight, too perfect. A groove.

He leaned closer, curious. Slipped his fingers into the gap and pulled hard. With a sharp sound, a small panel gave way, revealing a hidden cavity within the stone.

Inside, wrapped in a cloth that smelled of mold and salt, was a book.

Not a port ledger, not a ship’s log. A leather-bound book, dark and worn, but surprisingly intact.

Thalen took it with trembling hands. The rope fell to the ground without him even noticing.

His heart was pounding.

He sat back down on the dock with the book in his hands. Slowly, he opened it. The pages were filled with symbols he didn’t recognize: not letters, but signs, curves, geometric figures that seemed to shift under the flickering lantern light.

It was heavy. Ancient.

And as he turned the pages, for the first time in days, Thalen felt something.

Not hope, not fear.

But the clear, undeniable sensation that this book had been waiting for him for a very, very long time.

The pages opened with a dry rustle, as if they were alive. There was no wind in the boathouse, yet the dust rose from the stagnant air, floating slowly, dreamlike.

The runes inside the book seemed etched into metal rather than inked on paper. They weren’t mere symbols: they pulsed, faintly, like veins beneath skin.

Thalen gripped the book with his calloused hands, his breath uneven. He didn’t know that alphabet — no one did — and yet his mind began to form meanings.

The letters spoke to him.

And with the words came the visions.

Thalen’s eyes glazed over, and suddenly he was no longer in the boathouse but elsewhere, suspended in a memory that wasn’t his.

He saw a vast plain covered in armies. Thousands of warriors, banners torn by the wind, drums beating a rhythm of death. Siege engines as large as houses moved forward through black smoke.

Then, the ground trembled.

A crack opened, thin as a hair, then wider and wider, splitting the earth in two.

The noise of battle stopped. Everyone turned to look.

In an eerie silence, the ground folded in on itself and collapsed, forming a perfect crater. From its center rose a deep sound — a slow beat, like the heart of a giant.

The Abyss had been born.

The images came faster now, like a storm. People falling to their knees, shouting prayers; others running as if the world were ending; generals throwing themselves onto their swords rather than face what was happening.

Thalen staggered, but the book refused to close.

And as he stared, something in his body began to change.

First a tingling in his fingers, then a warm sensation climbing up his arms, shoulders, spine. The chronic pain in his knees vanished. His back straightened on its own.

He looked at his hands: the swollen veins were gone, the skin was tighter, younger. He felt stronger, more alive than he had in years.

And then he saw it.

A black figure, tall, slender, darker than the darkness around it.

It had no face, only two white slits where its eyes should have been.

And the laughter.

A laughter that did not seem meant to be heard by human ears. Long, warped, like metal bending under immense pressure.

The fisherman dropped the book, screaming. The runes went dark, the air grew heavy again, the boathouse silent.

He stayed there, panting, drenched in sweat, heart hammering.

Only then did he realize he was crying — hot tears he hadn’t shed in years.

For a long moment, he stared at the closed book on the floor.

One thing was certain: he no longer had the courage to touch it.

Not that night.

But as he sat heavily on the bench, a new fear gripped his chest: the fear that he wouldn’t be able to resist the temptation to open it again.

For the first time since his sons had died, he didn’t think about the rope.

He still had something left to understand.