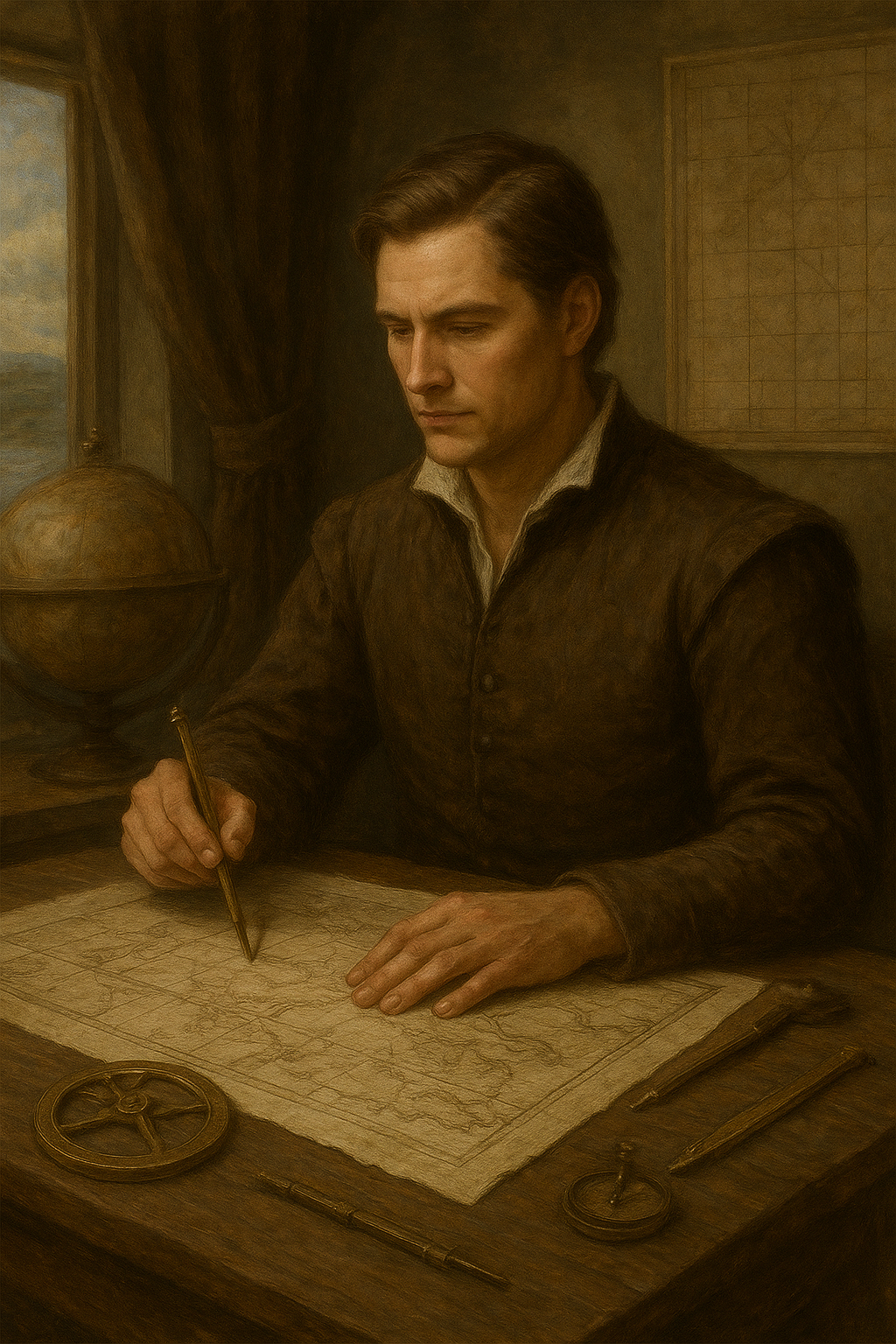

Kaelir Veynn was not a soldier, nor a colonist driven by dreams of glory. He was a cartographer, the most renowned of the Republic, chosen for a task that intertwined science and ambition: to redraw the wild coasts of the New World with surgical precision. At the head of a team of five cartographers, each with complementary skills, Kaelir led with the calm authority of someone who knew that a single mistake could cost lives.

He was surrounded by instruments that felt like extensions of his own body. His parchments, worn by ink and salt, were the fruit of months of work: lines traced with brass tools – magnetic compass, polished sextant, hourglass with grains fine as ash – and techniques he had refined himself, blending astronomy, geometry, and the study of marine currents. He used dead reckoning to estimate position when the stars were hidden, and a rudimentary cross-staff to calculate longitude, an art still uncertain in those unpredictable waters.

In recent years, he had honed methods inspired by ancient navigators: dead reckoning based on speed and heading, and astronomical observations with his rough cross-staff to fix longitude – imperfect but vital in these seas.

Kaelir’s team was a mosaic of talents: Lirien, a young astronomer obsessed with the constellations of the New World; Torren, a former sailor who read currents like lines of poetry; Syla, a draughtswoman able to turn numbers into elegant curves; Merrik, the eldest, an expert on seabeds and hidden reefs; and Veyra, Kaelir’s younger sister, skilled at transforming data into maps that looked like works of art. Together, they had traced hidden bays and treacherous inlets, noting every jutting rock, every current deviation that could swallow a fleet. Each stroke was measured with a lead line to sound the depths, verified by trigonometric calculations, and inscribed with the precision of those who knew that a map could decide the fate of an empire.

For months he had sailed the coasts of the New World, charting every hidden bay, every treacherous inlet, every reef that could tear a hull apart, every current that could drag a fleet astray.

He knew the political weight of his work: the Republic craved not only maps, but keys for conquest. Every safe harbor could become a fortified outpost, every river a golden vein for commerce. His parchments were silent weapons, seeds planted for an empire’s expansion.

But Kaelir did not feel like an instrument of power. As he studied those wild coasts, with the salty air clinging to his clothes and the wind cutting his face like a cold blade, he felt a deeper connection. To chart the world meant to honor it, to capture its essence beyond politics. That was why he noted details the generals would dismiss: the erratic flight of migratory birds signaling shifts in the wind, the change in sand colors – from blinding white to volcanic gray – hinting at underground currents, the iridescent glow on rocks at sunset, as though the land itself breathed light. Those were the true treasures: fragments of a living, mysterious continent.

It was late morning when their caravel, the Silver Light, was dragged by a treacherous current into “the belt.” That stretch of sea, a few kilometers wide, was wrapped in legends whispered by Calemir’s sailors: waters haunted by colossal creatures that dragged ships into the abyss, or brushed against them with ghostly curiosity. Kaelir, bent over a parchment, looked up and met Lirien’s gaze through her spyglass. “We’re too close,” she said tensely, lowering the instrument. “This is the belt. They say the sea here… looks back at you.”

Kaelir scoffed, shaking his head, though sweat trickled down his back despite the dawn’s chill. “The people of the New World are full of primitive fears,” he thought, gripping his quill until his knuckles whitened. “First the Hun, land monsters invented to frighten children, and now sea beasts. Nonsense to explain the unknown.” His scientific mind seethed with irritation: such tales were just rationalizations for natural phenomena – sudden whirlpools, pods of whales brushing against hulls, or optical illusions from coastal fog. All explainable, all measurable.

And yet, as the wind pushed them inexorably into those cursed waters, a shiver coiled up his spine. The sea had darkened – not from the brightening sky, but as if it swallowed light itself, a dull, bottomless black that reeked of rot and forgotten depths. The Silver Light rocked gently, not from any visible wave, but from something passing beneath the hull – a light, probing touch that made the timbers resonate like a muffled drum. Kaelir’s heartbeat quickened, echoing in the silence broken only by groaning ropes and a distant gull’s cry.

He forced himself to stay calm, notebook in hand. “Anomalous movement beneath hull. Unexplained oscillation with no visible wave or wind. Possible moving mass – school of fish or thermal current?” He leaned over the railing, the damp wood cold beneath his palms, staring into the water. Nothing: only that oily black veil that swallowed every glimmer.

Torren clung to the railing, face pale. “That’s no current, chief. Something brushed us. I can hear the wood strain.” Beside him, Syla dropped her pencil, her eyes wide. “That isn’t natural,” she whispered.

Kaelir steadied his voice. “Back to work. We won’t be spooked by stories.” Yet as he inhaled the briny air, tinged with a metallic trace like distant blood, he couldn’t silence the unease. “Write it all down,” he told them. “If it’s a phenomenon, we’ll explain it. If it’s a creature, we’ll map it.”

He resumed his calculations, but a cracking sound tore his focus away – deep, like branches breaking in a storm, coming from the nearby shore. Lifting his gaze, he saw trees sway, not from a landslide, but pushed aside by a living force. Whole trunks shifted, lifting clumps of wet soil and sprays of leaves.

They were Hun. Towering, furred colossi emerged from the forest, pelts soaked and dripping with muddy water. Their amber eyes gleamed under heavy brows, and their ponderous steps made the ground tremble, sending ripples across the sea around the Silver Light. The air filled with a musky, primal stench, tinged with salt and decay, as the creatures waded into the water, as though the sea were part of their realm.

The crew froze. Lirien dropped her spyglass, clattering across the deck. Torren seized an oar, as if it could fend off giants. Syla stifled a scream with her hand. Only Merrik kept writing, his pen trembling slightly. Kaelir, heart pounding like a hammer, forced himself to observe. This was no random migration. The Hun moved deliberately, ritualistically, as if following a path drawn centuries ago.

Scanning the bay, Kaelir noticed its unique shape: the only point on the coast where the forest met the sea without beaches or cliffs. The trees grew directly into the water, roots exposed like veins, forming a natural corridor. Beyond, dark mountains loomed, their peaks tearing the clouds like ancient claws. “Look at the coast,” he said firmly. “It’s a passage. The forest is a corridor between land and abyss.”

Veyra, trembling, sketched the bay, marking the gap. “A portal,” she whispered. “They’re guarding something.” Kaelir nodded, jotting in his notebook: Charcoal circle: forest meets sea. Mountains to the northeast. Hun moving toward water. Possible ritual route.

He thought of tavern tales: vanished ships, hulls dragged down, colossal shadows beneath the waves. Not myths, but fragments of truth.

That point had to be mapped. The Republic would send fleets. Explorers.

Kaelir turned toward the sea. The shadow under the surface had sharpened: a colossal mass moving slowly, parallel to the ship. Not a current. Not fish. An Hun. Its indistinct, immense form seemed to drink in the dawn’s light, a hairy shadow stretching like a portent. An amber eye surfaced briefly, small compared to its bulk yet piercing, fixed on the Silver Light. Kaelir shivered – not from cold, but from the sense that the creature saw him not just as a man, but as a threat.

“We can’t stay,” Veyra pleaded. “Kaelir, we must leave. Now.” But before he could answer, the Silver Light shuddered, a deep groan as the hull cracked. An enormous arm – fur matted with brine, thick as an ancient trunk – tore through the keel with a crash that made Syla scream. Splinters flew as the limb rose above the deck, dripping black water reeking of rot and ancient death. An amber eye glared from the sea, the Hun’s colossal head rising, blotting out the newborn sun.

Torren swung his oar against the arm – a futile gesture that drew only a bitter laugh from Merrik, who kept writing. “We can’t fight this,” the old man said.

Kaelir seized the bottle from Veyra and hurled it into the swelling waves. The sea swallowed it with a sinister gurgle. “Find it,” he murmured, voice breaking – whether to the ocean or fate itself. Water surged onto the deck, icy against their legs, as the Hun’s arm moved with cruel slowness, ready to tear the ship apart.

Kaelir looked at his crew – Lirien clutching her spyglass like an anchor, Torren cursing the Hun, Syla sobbing, Merrik still writing, Veyra staring at him with desperate trust. He knew there would be no escape. But the map, at least, could survive, carrying the secret of that passage and the weight of what the Hun were guarding.